James, R, 1993, Linear Skin Rashes and the Meridians of Acupuncture. European Journal of Oriental Medicine, 1(1),42-46.

Abstract: A case of Lichen Striatus is described. A literature review of similar cases is summarised, with particular reference to the monograph of Blaschko, 1901. The relationship of linear skin rashes to the meridian concept is discussed. A direction for further research is proposed.

Keywords: Meridian, linear rashes, Lichen Striatus.

THE CONCEPT OF MERIDIANS IN ACUPUNCTURE has been subject to widely differing interpretations by commentators with differing backgrounds and orientation. As indicated by Porkert (1974), the character mo or mai is used in different contexts to mean: pulse, pulse-energy, energy-channel or blood-vessel. Translation with a narrow perspective leads to the idea of a system of ‘vessels’ through which energy ‘flows’ just as blood flows through arteries.

Indeed one worker (Bong Han, 1965) made an anatomical/histological search for the meridians and published detailed findings which have been quoted (Lawson- Wood, 1973) as proof of a material basis for meridians, but these findings have never been validated by other workers. Most workers do not take seriously the idea that meridians have a material form. Instead they are generally held to represent a set of functional relationships between active points on the surface of the body. To quote a widely respected author: “Channels should not be seen as ‘lines’ running in the body, but rather like areas of influence over a certain section of the body”. (Maciocia, 1989, p. 152).

In the absence of a material substrate for the meridians, some choose to dismiss the idea, finding it “…difficult to reconcile them with the principles on which the present day Western system of medical practice is based” (Baldry, 1989). One might wonder how the concept arose in the first place. They may be merely artefacts of the pattern of reflections from the skin under bright, oblique lighting (Macdonald, 1978), but I am assured by some acupuncturists that they can see the points and meridians in the aura, and I believe that the experience of feeling the energy at certain points is quite common, among acupuncturists I know. A more common explanation of how the idea of meridians arose concerns de qi, the sensation associated with needling acupuncture points. Sometimes this is a feeling of a flow in the body; if so, its course often seems to follow the meridians concerned. There have been a few reports (Naga- hama, 1950) of individuals who have an exaggerated experience of de qi, for example following a strike by lightning. It has even been possible to map the whole meridian circuit via such subjective reports. It may be argued that the subjects (being Japanese) had prior knowledge of the meridians and so imagined the feelings. Yet it also occurs in patients who had no knowledge of the meridians. I have seen this clearly in some of my own clients. The following case provides new food for thought.

Case-report

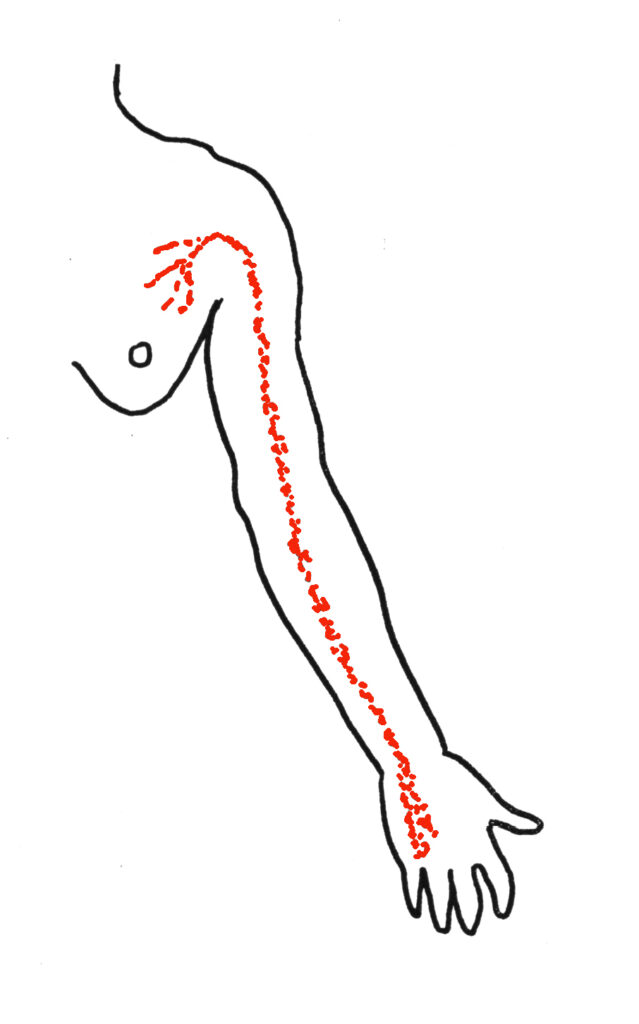

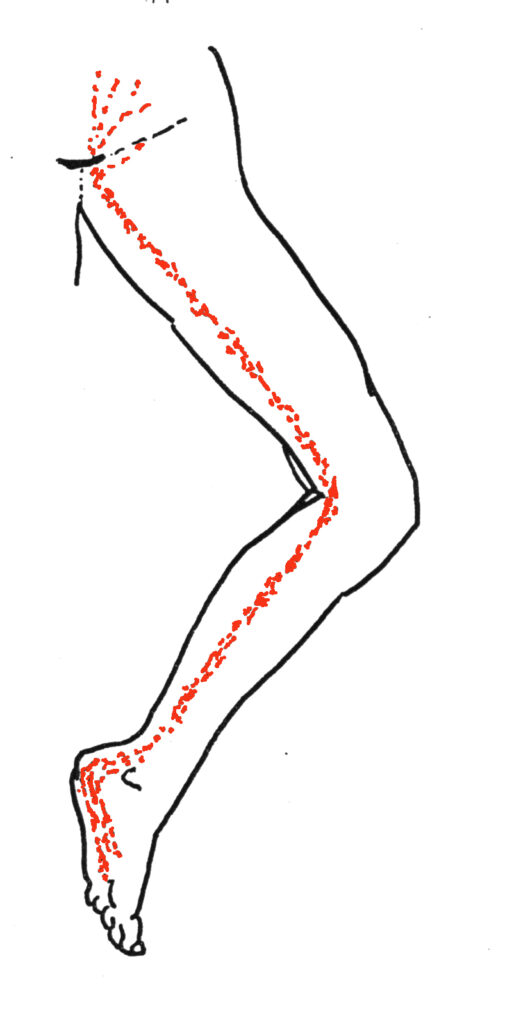

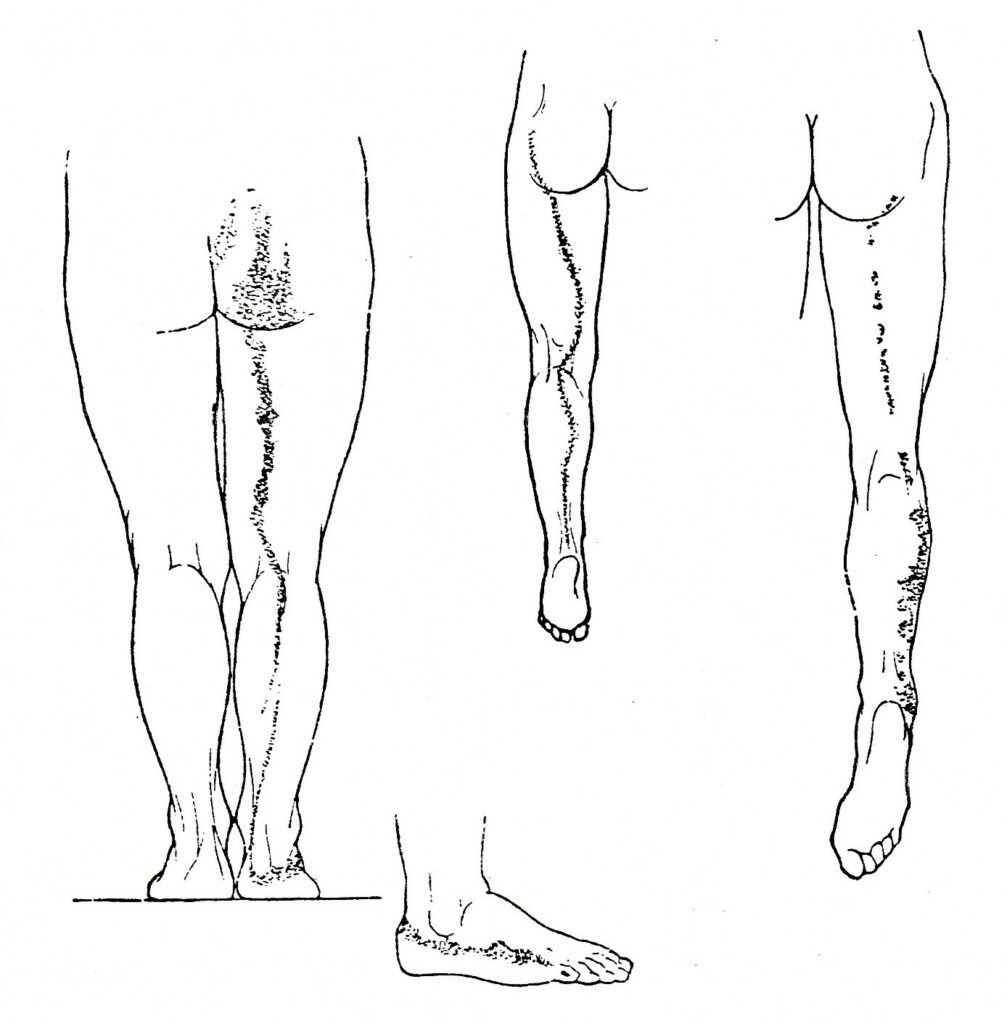

A 25 year old woman presented to the dermatology clinic of a London teaching hospital with an itchy, licheniform rash, which had been present for one month. It was distributed in two lines consisting of red, flat-topped papules a few millimetres across, clustered into lines of 0.5 – 1.0 cm width. The distribution of these lines is shown in Figure 1 (above). At the ends of each line the rash dispersed over a broader area, before fading out. Unfortunately no photographs were taken but the rashes were sketched carefully. She was given a diagnosis of Lichen Striatus and some Prednisolone tablets. On her return, one month later, the rash was gone.

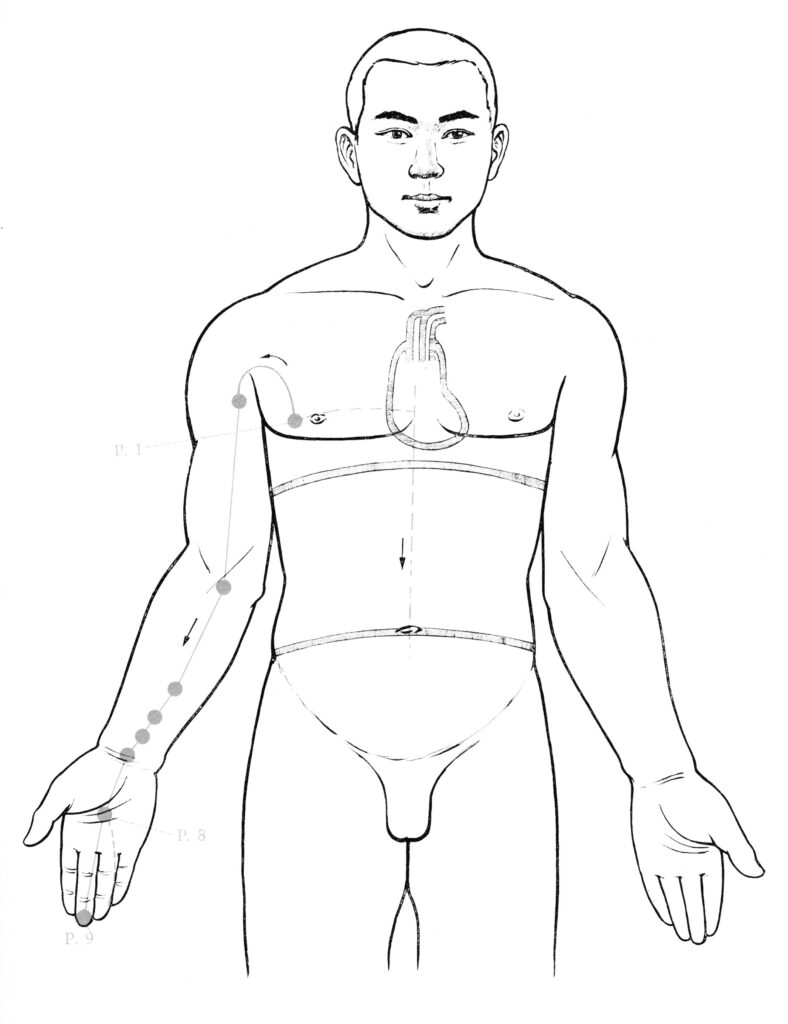

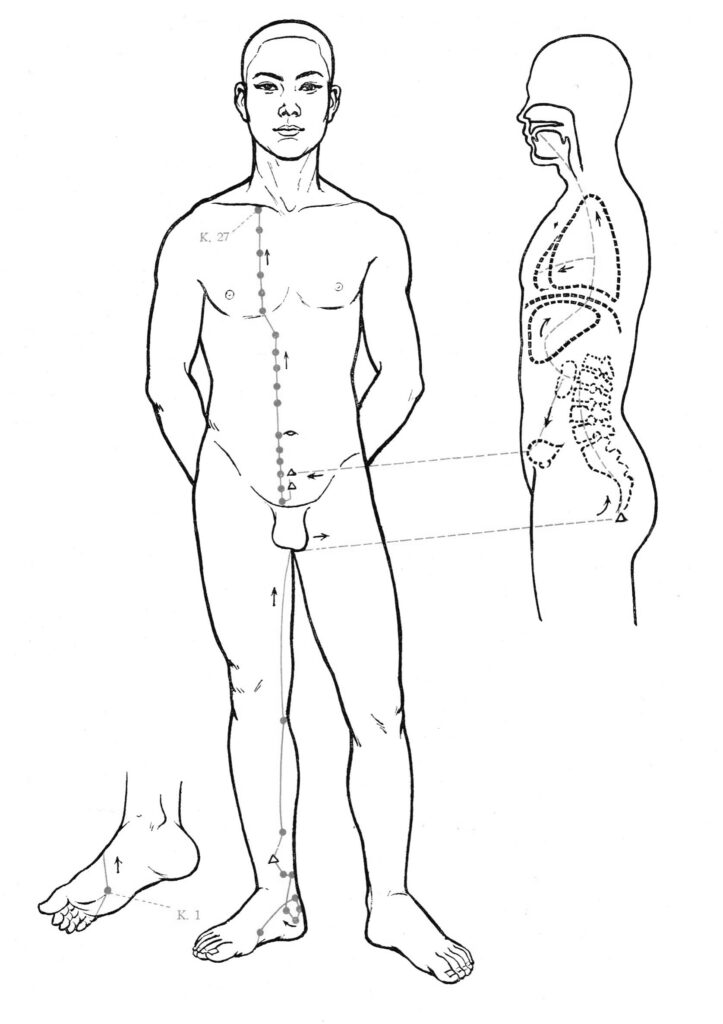

The distribution of her rash was discussed at length by the doctors and students present, who all agreed that no anatomical or physiological concept was appropriate to explain it. Any acupuncturist will be quick to notice that these lines correlate neatly with the course of the Kidney and Pericardium meridians. What is more these two are consecutive (numbers VIII and IX) in the diurnal energy circuit and are connected via a ‘deep pathway’ between the pubic area and the upper chest (Beijing College of TCM, et al, 1980). This is suggestive of a significant link between this rash and the meridians.

Linear rashes

I was inspired by this case to search this century’s literature for more examples of linear rashes. The recorded cases include various congenital naevi and linear manifestations of eczema, psoriasis, scleroderma, vitiligo, lichen planus and others. Much attention has been given to the clinical appearance and histology of the lesions and in some cases they are similar to non-linear examples of the same types of eruption. In many, however, the histology is non-specific and highly variable, giving rise to the idea that this phenomenon is a pattern of response, rather than a nosological entity. Reviewing the relationship of the reported rashes to the pathways of the meridians was difficult because in most cases the illustrations and descriptions are inadequate for comparison to be made. Fortunately, one worker included a collection of about 200 excellent drawings which clearly illustrate the distribution of rashes of all kinds (see Figure 2). Therefore my preliminary study was made with reference to this work (Blaschko, 1901).

Blaschko’s lines

Blaschko showed that linear and zoniform eruptions are not a unitary phenomenon, but may be subdivided into categories (Table 1).

| Herpes zoster | Congenital naevi | Acuired rashes | |

| Obviously linear | 1 | 5 | 35 |

| Obviously patchy | 55 | 55 | 15 |

| Equivocal | 3 | 20 | 10 |

| Totals | 59 | 80 | 60 |

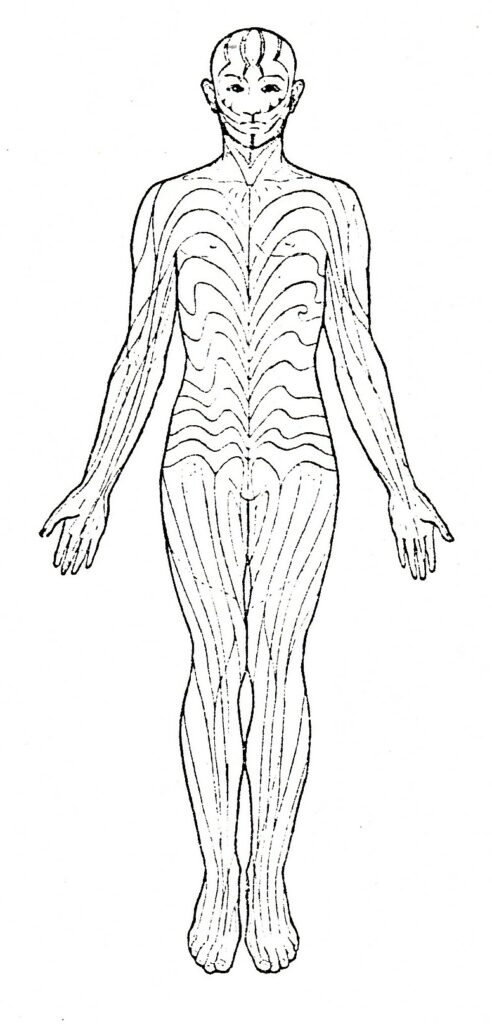

He was among the first to note that the zones of eruption of herpes zoster correlated with dermatomes. However, he was unable to offer an explanation for the peculiar distribution of the other rashes. He derived an abstract set of lines by drawing the rashes of his cases on a doll and then transfering them schematically onto charts (Figure 3).

Subsequently numerous hypotheses have been advanced to explain them: lines may run superficial to the course of blood-vessels or lymphatics, or peripheral nerve-trunks; they may correspond to the distribution of a particular cutaneous nerve, or spinal nerve; they may follow the boundaries of distribution of nerves (Voight’s lines) or the lines of junction between dermatomes; they may be related to embryonic patterns in the skin, such as the dermatomes, lines of cleavage of the skin (Langer’s lines) or hair- stream lines; or they may be a throw-back to the markings of animals. None of these holds up to inspection. In contrast to our anatomical understanding of herpes zoster, no theory explains all of Blaschko’s lines and the distribution of the majority of linear rashes remains unexplained. A recent review (Jackson, 1976) concluded that we have “…no answers to explain the pattern of Blaschko’s lines. …the inadequate term ‘loci minoris resistentiae’ is all we can offer”.

Meridians and Blaschko’s lines

The above reviewer had considered acupuncture meridians as a possible correlate of Blaschko’s lines (Jackson, personal communication). He rejected the idea, as those on the trunk do not fit. But if we look at Blaschko’s original data instead of his conclusions, some correlations do emerge. Blaschko derived his lines by including both naevi and acquired lesions. Yet they are quite different; naevi are congenital, permanent and tend to be multiple and patchy, while the others are transient and more often appear as simple lines (see Table 1, above). So I focused my attention on the acquired linear rashes.

Within this group it was clear that no one type of lesion had a greater tendency to form clear lines, although the manifestations of scleroderma and purpura seemed to have less tendency to do so (Table 2).

| Type of lesion | Number of cases | Number obviously linear |

| Lichenoid | 18 | 13 |

| Unnamed | 10 | 6 |

| Eczema | 8 | 6 |

| Scleroderma | 8 | 1 |

| Psoriasis | 7 | 4 |

| Purpura | 3 | 0 |

| Miscellaneous | 8 | 5 |

| Totals | 62 | 35 |

I was able, subjectively, to relate about half of the clearly linear lesions to the paths of the classical meridians. Certain meridians seem to be followed more than others, but there was no association between particular meridians and the nature of the eruption (Table 3).

| Type of lesion | Uncorrelated | Correlated with meridians |

| Lichenoid | 6 | 7 |

| Unnamed | 3 | 3 |

| Eczema | 3 | 3 |

| Scleroderma | 1 | 0 |

| Psoriasis | 2 | 2 |

| Miscellan’us | 3 | 2 |

| Totals | 18 | 17 |

Bl11 | K | HC | GB | Liv | Co | Sp | Dai mo |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | |||||||

| 1 | |||||||

| 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

Discussion

What does all this mean? A possible association has been illustrated, but not proven. What about the rashes which are clearly linear but do not correlate with meridians; do they disprove a link? I think not. As we have seen, subgroups may be discerned, which have different characteristics and explanations. Another possibility is that further correlations might be found by considering the distribution of other ‘energy paths’ such as the tendino-muscular meridians. I chose not to include these as they are less well charted. The appearance of the rashes is striking and the mind cries out for an explanation. How can we understand this, what does it mean, what does it tell us about life? Inevitably we seek an explanation in terms of our existing paradigm, or world-view, and in some cases this satisfies the need. For example ascending lymphangitis is explained at the simple anatomical level by relating the linear rash to a linear

structure under the skin – the lymph vessel. Another example is the shingles rash. Here the explanation is an anatomical concept of a higher order, the dermatome. But a search of the existing paradigm of reductionist, materialist medicine revealed no concept on any level capable of explaining the distributions of these other rashes. The temptation is therefore to ignore the phenomenon or to dismiss it as coincidence, or the work of imagination. Kuhn might point out that we have a situation where the observed phenomena no longer fit the paradigm, so a ‘scientific revolution’ might be imminent (Kuhn, 1970). Or maybe we are about to discover something new about how the body works, which we can integrate with the prevailing paradigm. Meanwhile the ancient paradigm of Chinese medicine offers an alternative framework for ordering our experience.

I feel this cognitive aspect has interesting implications regarding the role of acupuncture in the West, compared with China: it can be used to help patients to re-frame their experience in terms of a new (to them) set of concepts. There is a mutually supportive interplay between the conceptual input and the effects of the needling. Indeed in my clinical experience reframing alone is sometimes sufficient to facilitate healing – one might call it ‘No-needle technique’.

Consciousness is important in acupuncture at other levels also: – the level of cognition of the phenomena. The patient’s perception of a symptom will depend on their paradigm. The practitioner’s interpretation of it will depend on theirs. The choice of needling sites will be made with reference to these ideas.

- de qi. The patient who is conscious of this idea is more likely to expect, notice and report the experience. The patient who is not is more likely to dismiss it as an odd feeling and ignore it. Of course, as noted above, the former may well create the feelings with their imagination. Does this invalidate them or prevent them from being useful? I suggest not. Our consciousness is a model of our environments, both internal and external, and so will be pre-disposed to align itself with notions of higher validity.

- healing through meditation. In my experience clients may benefit a great deal from combining needle treatment with the use of breathing exercises and guided visualisation of energy flow. Whether this works generally, via the relaxation response, or specifically, in relation to the structure of the exercises, remains to be determined.

- placebo effect. Conventionally this has been presented as an either/or phenomenon; the effects of acupuncture were either ‘real’ or ‘placebo’. But, as Campbell has pointed out (Campbell, 1991), this dualism is misguided. The effects of needles and the effects of cognitive input, via higher neural mechanisms, are mediated via the same paths in the brain-stem and spinal cord. Their effects are inevitably interwoven and interactive.

In summary, I contend that the concept of meridians is not redundant. It is the best working hypothesis we have to explain a number of phenomena, including the linear rashes described above. Clearly, the association is worthy of further study. We need to identify many more cases of the phenomenon, and examine the patients while the rash is present with the above ideas in mind. Such cases are uncommon, so the study is likely to be prolonged. I offer the following outline protocol (see separate box) for the study of any new cases, and I would be most grateful to be informed of any, at the earliest possible opportunity.

Research proposal

When an apparently linear rash has been noticed, it should first be examined by a doctor/dermatologist, who would classify it in the usual way and then consult a meridian map to identify any meridian with which the rash might correlate. The rash should then be hidden from view and the acupuncturist would mark the suspect meridian and the adjacent ones on the opposite side of the patient’s body. Photographs could then be taken from the same angles on each side and an objective comparison may be made.

References

- Baldry, P. E.. (1989). Acupuncture, Trigger Points and Musculoskeletal Pain. Churchill Livingstone.

- Beijing College of TCM, et al. (1980). Essentials of Chinese Acupuncture. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

- Blaschko, J. (1901). Die Neven- verteilung in der Haut in ihrer Beziehung zu den Enkrankungen der Haut. Beilage zu den Verhand- lungen der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft VII Congress, Breslau.

- Bong Han, Kim. (1965). Kyungrak System and Theory of Sanal. Proc. Acad. Kyungrak of D.P.R.K., No 2. Pyongyang, Korea: Med. Science Press.

- Campbell, A. (1991). Hunting the Snark: the quest for the perfect acupuncture placebo. Acupuncture in Medicine IX (2), 83-84.

- Jackson, R. (1976). The Lines of Blaschko: a review and reconsideration. Brit. J. Dermatol. 95, 359-360. Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

- Lawson-Wood, D. & J. (1973). Acupuncture Handbook. Wellingborough, Northants: Health Sciences Press.

- Macdonald, A. Quoted in Pain Topics, 1(4) 1-5, Feb 1978. Maciocia, G. (1989).

- The Foundations of Chinese Medicine. Churchill Livingstone. Nagahama, Y. and Maruyama, M. (1950). Research of Meridians. Tokyo: Kyorin Shoin. Quoted in Motoyama, H. (1975). Do meridians (keiraku) exist, and what are they like? Research for Religion and Parapsychology 1(1), 1-48.

- Porkert, M. (1974) Theoretical Foundations of Chinese Medicine. Cambridge, Massachusetts: M.I.T. Press.

| Acknowledgement: I thank Dr T. W. E. Robinson, of UCH, for his guidance and help. |

Footnote

- Different abbreviations for the meridian names have been used in different contexts. Nowadays I use those recommended by the WHO. The relevant equivalents are: Bl = BL (Bladder), K = KI (Kidney), HC = PC (Pericardium), GB = GB (Gall bladder), Liv = LR (Liver), Co = LI (Large intestine), Sp = SP (Spleen), Dai mo = Girdle meridian. ↩︎