I do not see holism as inherent in acupuncture but as an approach to aspire to in practice.

The word “holistic” has often been misappropriated in recent years and used, often for commercial purposes, to give kudos to various fringe practices. I would like to rescue and renovate the concept by exploring in some depth how it usefully informs my practice of acupuncture. We can use different models of holism to explore this.

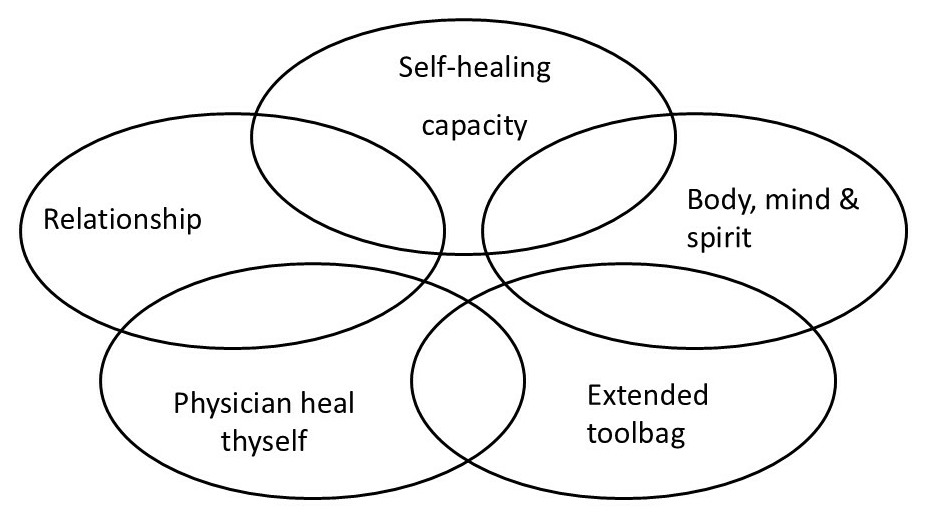

First, let’s look at Patrick Pietroni’s Five Facets model.

Pietroni1 presented this way of describing holistic medicine at the inaugural conference of the BHMA (British Holistic Medical Association) in 1982. Five facets of holistic practice are described; they are not exclusive categories but overlapping aspects of practice to be considered.

How do I apply this to acupuncture?

Promoting Self-healing

Sceptics often dismiss acupuncture as mere placebo, lacking any specific effect. This is based on simple black/white thinking leading to the misconception that the needling activates discrete mechanisms to achieve discrete effects which are independent of the more general effects. But we now know that acupuncture causes a variety of complex physiological changes at a number of levels. These include changes in the same mechanisms that are involved in (spontaneous) self-healing. Others have pointed out that the placebo response is valuable; belief in the intervention promotes self-healing. We should make as much use of it as we can, while trying to ensure that our “specific” interventions do not do the opposite.

In addition we can make use of other strategies to promote self-healing such as diet, relaxation, breath-work and visualisations (such as picturing the flow of breath/Qi through the body as needed).

The focus in on facilitation, rather than treatment. Where treatments are being offered by the practitioner, the therapeutic intention is to catalyse a movement, balancing or harmonisation of the client’s Qi. Sometimes it may be appropriate to teach the client (or their family) how to continue the treatment at home, eg. using massage, moxibustion or even needles.

Body-Mind-Spirit

Holism is often defined simply as taking into account the “whole person”: body, mind and spirit. Yet, from a biomedical angle, acupuncture is simply a physical technique performed on the physical body of the client so why would we call it holistic? Well, “stress” is a whole person model within the biomedical frame and acupuncture is often reported to alleviate stress.

However there are also mental, emotional and spiritual perspectives available. From a traditional angle, Chinese medicine is a variety of techniques with a common aim: to restore harmony of the Qi. Some of these techniques involve physical intervention (acupuncture, massage, herbs), some mental (advice about lifestyle), some spiritual (meditation). Some are hard to classify in this trinity; Qigong healing is a technique where the Qi of the practitioner is directed so as to have a therapeutic effect in the client. Should we see this as a spiritual technique, akin to Spiritual Healing, or should we hypothesise Qi as a form of energy to be investigated by physicists?

Sometimes the simple consideration of these alternative views is sufficient for the client to ‘reframe’ their experience, which may be all they need, to move past a state of stuckness. The Five Phases2 model seems particularly useful in this way transcending, as it does, the mind-body dualism.

Another way of considering mind-body interactions comes from the neoReichian therapies in the West. They use concepts of bio-energy (orgone, libido) that bear significant similarities to the acupuncturists ‘Qi’ and such concepts may be used to guide acupuncture treatments.

Focus on change and development may be seen as a spiritual perspective. A pain may be viewed as “change trying to take place”; emotional problems as a challenge to be overcome. Rather than attacking these phenomena as symptoms to be suppressed, acupuncture can be a catalyst for change and development.

Extended range of interventions

Acupuncture is, of course, an extension to the range of conventional practice, even if it consists only of sensory stimulation using needles. But it is also used with related interventions such as massage, stretching, electro-stimulation, moxibustion. Then there are self-help activities such as breathing, exercise, diet and meditations.

Beyond physical interventions are mental ones; a range of ideas from physiology to 5-phases and Qi-energetics can be used in this way. Sometimes “acupuncture” can even be a talking therapy.

Doctor-Client Relationship

The conventional view is of client and practitioner as two separate physical entities; they are not connected but interact. However, this ignores the fact that we exist in a continuous energy field. Even without considering the strange notion of Qi, we know that the heart generates a strong electromagnetic field that can be detected at a distance from the body and that the fluctuations in this field are affected by mental state. Being in the same room with someone is enough for interaction of our electro-magnetic fields; for example for a recipient to “entrain” to a healer’s state of inner harmony. From this viewpoint of individuals as energetic and resonant beings (rather than two materially separate entities), their interconnectedness becomes apparent.

We all know that quality of touch is important. Even so, in medical school I was trained to use touch only to gather information or to perform physical interventions; clients might occasionally refer to someone having a ‘nice touch’ but this was never referred to by my trainers. There have been numerous studies showing the importance of this; personally, I am intrigued by the work of Manfred Clynes on Sentics.

Acupuncture inevitably involves touching the client but more – by inserting a metal needle (an electrical conductor) through the skin into the body fluids we have a unique opportunity for electromagnetic interaction; how can we optimise the effects of this? The Chinese concept of Yi is relevant here. This is usually translated as “therapeutic intention” and refers to the practitioner’s state of mind as they perform a treatment.

Another aspect of the relationship is its client-centredness. Rather than imposing a (diagnostic) model on the process, I aspire to go with the flow. The motivation comes from the client and their Qi is the motive force.

Physician Heal Thyself

The harmonious, balanced state of the practitioner is valued highly by traditionalists. The importance of this is apparent if one considers the resonant oneness of the Client-Practitioner dyad [see above]. It is also reinforced by studies revealing induction of patterns in EEGs during healing.

Techniques such as Tai Chi, Qigong and Do-In may be practised, as well as general health maintenance.

Beyond healing, the practitioner (like the client) is seen to be a developing person, rather than a mere technician. The therapeutic relationship has the potential to be transformative to both of the participants, if they are open to such change. The practitioner has a responsibility to be aware of this and to participate at some level, whether by reflective professional development or spiritual practice.

Another model of holism is John Heron’s 4 dimensions [continued here]

Footnotes:

- Pietroni, P. C. (1984). Holistic medicine – new map, old territory. British Journal of Holistic Medicine 1: 3-13.

- The term ‘Five Elements’ is commonly used but, for some, this conjures up the counterproductive notion of four elements from ancient Greek philosophy and alchemy. As well as being vulnerable to labelling as ‘medieval’ this notion refers to component parts of something – a materialistic slant. I prefer ‘Five Phases’ with its connotations of dynamism and interchange.