What’s in a name?

When I established my acupuncture practice, in 1978, I chose this name to reflect my values and aspirations, which had clarified during my years of medical training.

Integration is about wholeness.

Putting things back together. The opposite of differentiation, separation. Our society suffers because of separation. Separation of mind from body – psychologist from surgeon. Separation of people from their environment. Separation of individuals from a sense of meaning.

Integrity means:

being whole, honest, consistent, true, at one with oneself. Achieving at-one-ment.

Self-healing.

Naturally maintaining the integrity of the self. Autopoeisis.

Integrative, not integrated.

We are not there yet. It is ongoing, a process not a thing.

Integrating the best of both.

Your wisdom and mine. East and West. Orthodox and Alternative. Science and art. Evidence and relevance. Tradition and innovation.

Integrating with, not incorporating into.

Healthcare.

A focus on health, not pathology. Possibilities, not problems.

A focus on care, not ‘fixing’. Being with. Witnessing.

Not ‘medicine’ with its pharmaceutical implications – I get more job satisfaction from helping people to come off drugs, than I would from helping them to obtain them.

Why is the name important?

When I first studied acupuncture it was called just that. Its essence was puncturing the skin with needles for beneficial effect: ‘acu-puncture’.

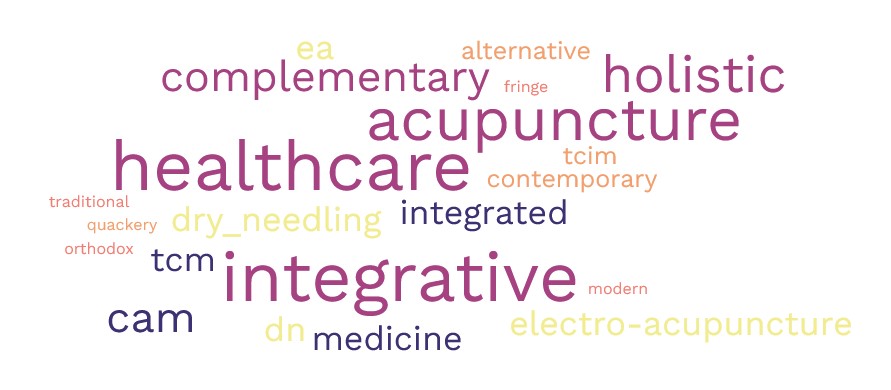

But the prevailing attitude in orthodox circles was dismissive and hostile. Acupuncture was bunched together with other ‘disreputable’ activities like phrenology and iridology and dismissed as as ‘fringe medicine’ or ‘alternative’.

Later the term ‘complementary medicine’ was introduced. A group of healers belonging to the National Federation of Spiritual Healers had been working alongside some open-minded GPs and this service was very popular with patients. They wanted to make it more widely available but encountered resistance from the medical establishment. To counter the objections, they made two things very clear: the first being that they did not make a diagnosis. This process was sacrosanct to the doctors; the healers had to make it clear that they had no designs on the magic words of the orthodoxy. The second was that they were not offering an alternative to general medicine. They were not trying to steal patients away. Their service was complementary.

The term caught on, and may have helped in reducing the hostility that prevailed at the time, between orthodoxy and the rest.

My own position was that our offering was BOTH complementary and alternative. I was at the Isis Centre for Holistic Health in Tottenham at the time1. Nearly all our clients were already receiving orthodox healthcare – but it wasn’t enough. In one way or another, it was failing to address their issues. Perhaps they couldn’t get a diagnosis, so no treatment was forthcoming. Or the treatment had not worked. Or it was unacceptable due to adverse effects. So we offered a range of alternatives to orthodox medicine and, by doing so, our service was complementing what NHS was offering. Not either/or but both/and – the best of both worlds.

In time the term ‘CAM’ (complementary and alternative medicine) took over and has become reified – an example of a word-without-a-thing that has become a thing in itself. Many people now bandy about ‘CAM’ as if it is a real thing.

It is as if acupuncture exists no longer as itself, but as part of a job-lot in comparison to the orthodoxy. Thus it came to be seen in the shade of orthodox medicine, to be judged by the same standards. The same could be said of other distinct healing disciplines such as: herbalism, osteopathy or homeopathy. By subsuming them all under the same umbrella (even though the only thing they had in common is NOT being orthodox medicine) they are reduced to lowest common denominators. Their unique attributes are ignored. They are disempowered.

Meanwhile, a new meme appeared: Holism. I found this concept nicely encapsulated the ideas and attitudes that I valued. Excellent work was being done by the British Holistic Medical Association, and published in their journal Holistic Medicine (now Journal of Holistic Healthcare and Integrative Medicine). Sadly, the label soon became co-opted as a catch-all equivalent to ‘CAM’, and lost its radical connotations. Snake oil was now available in a range of ‘holistics’. A new word was needed to avoid that taint.

Up stepped ‘integrated’, giving us ‘integrated medicine’. But, to me, this wording implies a practice where orthodox medicine has come along and incorporated other therapies into it. I don’t feel comfortable with that, so I am glad of the choice I made, all those years ago.

Footnote:

- Isis as in the goddess of healing. Not to be confused with the river in Oxford nor, of course, the jihadi group of later notoriety.